Laos Scho0l Visit - Nov 2010

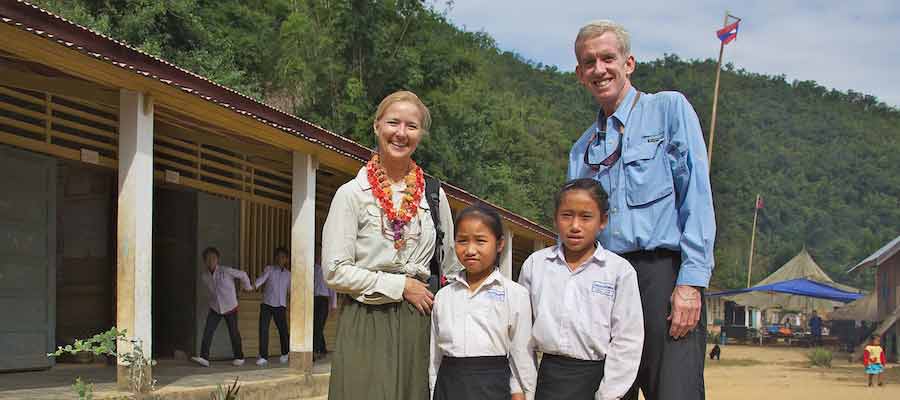

Opportunity For All co-founders Al O'Connor and Anne Studabaker traveled to northern Laos in November, 2010 to visit Room to Read's Laos field office and three new Opportunity For All schools in Northern Laos. Here's Anne's description of what they found:

Laos Trip Video

Somphet Phongphachanh, Room to Read’s country director in Laos with Anne

Al & Anne with Room To Read's Country Staff

ROOM TO READ LAOS as of November, 2010

Education in Laos at a Glance

Primary schools in Laos in 2005 8,654

Primary Schools in Laos in 2010 8,968

Primary school students in 2010 900,000 est.

Secondary Schools in Laos in 2010 1,000 est.

Room to Read Laos -- For the Record, 2005 - 2010

Reading rooms built 617

School Rooms 172

Girls Education Program 1,075 enrolled, 9 have dropped out

Local language books published 82

Local language posters published 16

Literacy pilot program 28 schools

Education in Laos at a Glance

Primary schools in Laos in 2005 8,654

Primary Schools in Laos in 2010 8,968

Primary school students in 2010 900,000 est.

Secondary Schools in Laos in 2010 1,000 est.

Room to Read Laos -- For the Record, 2005 - 2010

Reading rooms built 617

School Rooms 172

Girls Education Program 1,075 enrolled, 9 have dropped out

Local language books published 82

Local language posters published 16

Literacy pilot program 28 schools

VIENTIANE FIELD OFFICE

November 26, 2010

We started of our journey flying into Vientiane, the capital of Laos where Room to Read's Laos field office is located. We had a Friday afternoon appointment to meet with the entire staff where we hoped to hear about the work Room to Read in Laos. It was a great meeting! After 3 hours of back and forth, we had learned the following:

Somphet Phongphachanh, Room to Read’s country director in Laos, is a vibrant woman whose passion for educating the poor children in her country slams into you when you meet her. Where so many of her countrymen are laid back and quiet, Somphet could rival a New Yorker for fast talking. With Somphet, however, there is no hidden agenda, just focused determination to make a difference. And for her, that means education.

It is no wonder then, that Room to Read Laos has accomplished so much in just five years. Under Somphet’s direction, the NGO has built 617 reading rooms, launched a literacy pilot program, published 82 local language books for grade schoolers (five of which have won awards from the government), enrolled 1,075 girls in their scholarship program and, of course, built 172 schools.

Since the Lao government currently only requires education through the fifth grade, that is where Room to Reach focuses its school program. And because in many poor, rural areas even this much education is not always available (or parents can’t afford it), the NGO focuses on the hardest to reach and poorest provinces. Small wonder that Room to Read Laos finds one of its greatest challenges to be hiring quality people in the field.

Building Schools

Primary schools in Laos are broken into lower (grades 1-3) and upper (grades 4 and 5) schools. An incomplete primary school is grades 1-3 only; a complete primary school is grades 1-5. Secondary schools are grades 6-9; high school, 10-12.

In the poorer, most remote communities, where a village has only an incomplete primary school, education often stops with third grade because the children would have to commute too far on a daily basis or be housed in a dorm, which is not ideal and expensive for the family.

Last year, 67 communities applied to Room to Read for a primary school; only 30 were approved. Room to Read conducts a survey of the applying communities, evaluating their commitment to education, to the project and to the follow-up and maintenance necessary for a successful school.

Once a project is approved, Room to Read transfers money to the community, which manages the building process. Room to Read field personnel regularly meet with the village building committees to review progress and offer advice if needed. Where a community can save money, they are encouraged to buy more desks, chairs and school room supplies. (Note: books that Room to Read publishes are provided free to each community, with new titles and replacements supplied annually.)

Reading Rooms

Although Opportunity For All’s focus in Laos has been schools, Somphet personally believes that the reading rooms are needed more. “I want to open the world to these poverty stricken fellow citizens,” she says. “I would like to have a library with every school, but the funding is not always there. Funds come into the country earmarked by donors,” for a school, a reading room, a girl’s scholarship etc.

One of Room to Read’s challenges is to teach communities about the concept of a lending library, how to care for the books, check them out/in. “In some cases, teachers working as librarians wouldn’t let kids have access to the books because they are a rare and precious commodity,” says Somphet, adding that field workers now show communities a different perspective. “They explain how reading makes better citizens -- people who can make better choices, who know how to get information and use it for good,” she says.

Literacy

What has also become clear from field work is that many children in grades 1-3 are not learning how to read. Official, government testing does not occur until fifth grade. To improve the reading ability of all primary students, Room to Read Laos is testing a literacy program: publishing materials and teaching teachers how to teach reading.

2010 was the first year for the pilot program, launched in 28 schools, 34 classrooms, and was offered for first grade teachers only. At a cost of $100,000 a year, they hope to expand the program to second grade teachers in 2011.

Just Girls

Room to Read Laos is making inroads in one other area: girls’ education. Through scholarships, they hope to “level the playing field with boys,” Somphet explains, pointing out that boys take priority when a family is paying for education. A boy will, after all, grow up to take care of his parents. A girl, who is often married off at age 13-14, will move to her husband’s family and take care of them. In addition, this is Room to Read’s effort to keep girls out of the sex trade.

Note: There are other NGOs in Laos that build schools, including organizations from the UN, the EU and Japan.

We also learned that Room to Read has a staff in Laos that is passionate about what they do. We left the meeting in the early evening in preparation for a full day of travel by both air and 4-wheel drive as we headed north.

November 26, 2010

We started of our journey flying into Vientiane, the capital of Laos where Room to Read's Laos field office is located. We had a Friday afternoon appointment to meet with the entire staff where we hoped to hear about the work Room to Read in Laos. It was a great meeting! After 3 hours of back and forth, we had learned the following:

Somphet Phongphachanh, Room to Read’s country director in Laos, is a vibrant woman whose passion for educating the poor children in her country slams into you when you meet her. Where so many of her countrymen are laid back and quiet, Somphet could rival a New Yorker for fast talking. With Somphet, however, there is no hidden agenda, just focused determination to make a difference. And for her, that means education.

It is no wonder then, that Room to Read Laos has accomplished so much in just five years. Under Somphet’s direction, the NGO has built 617 reading rooms, launched a literacy pilot program, published 82 local language books for grade schoolers (five of which have won awards from the government), enrolled 1,075 girls in their scholarship program and, of course, built 172 schools.

Since the Lao government currently only requires education through the fifth grade, that is where Room to Reach focuses its school program. And because in many poor, rural areas even this much education is not always available (or parents can’t afford it), the NGO focuses on the hardest to reach and poorest provinces. Small wonder that Room to Read Laos finds one of its greatest challenges to be hiring quality people in the field.

Building Schools

Primary schools in Laos are broken into lower (grades 1-3) and upper (grades 4 and 5) schools. An incomplete primary school is grades 1-3 only; a complete primary school is grades 1-5. Secondary schools are grades 6-9; high school, 10-12.

In the poorer, most remote communities, where a village has only an incomplete primary school, education often stops with third grade because the children would have to commute too far on a daily basis or be housed in a dorm, which is not ideal and expensive for the family.

Last year, 67 communities applied to Room to Read for a primary school; only 30 were approved. Room to Read conducts a survey of the applying communities, evaluating their commitment to education, to the project and to the follow-up and maintenance necessary for a successful school.

Once a project is approved, Room to Read transfers money to the community, which manages the building process. Room to Read field personnel regularly meet with the village building committees to review progress and offer advice if needed. Where a community can save money, they are encouraged to buy more desks, chairs and school room supplies. (Note: books that Room to Read publishes are provided free to each community, with new titles and replacements supplied annually.)

Reading Rooms

Although Opportunity For All’s focus in Laos has been schools, Somphet personally believes that the reading rooms are needed more. “I want to open the world to these poverty stricken fellow citizens,” she says. “I would like to have a library with every school, but the funding is not always there. Funds come into the country earmarked by donors,” for a school, a reading room, a girl’s scholarship etc.

One of Room to Read’s challenges is to teach communities about the concept of a lending library, how to care for the books, check them out/in. “In some cases, teachers working as librarians wouldn’t let kids have access to the books because they are a rare and precious commodity,” says Somphet, adding that field workers now show communities a different perspective. “They explain how reading makes better citizens -- people who can make better choices, who know how to get information and use it for good,” she says.

Literacy

What has also become clear from field work is that many children in grades 1-3 are not learning how to read. Official, government testing does not occur until fifth grade. To improve the reading ability of all primary students, Room to Read Laos is testing a literacy program: publishing materials and teaching teachers how to teach reading.

2010 was the first year for the pilot program, launched in 28 schools, 34 classrooms, and was offered for first grade teachers only. At a cost of $100,000 a year, they hope to expand the program to second grade teachers in 2011.

Just Girls

Room to Read Laos is making inroads in one other area: girls’ education. Through scholarships, they hope to “level the playing field with boys,” Somphet explains, pointing out that boys take priority when a family is paying for education. A boy will, after all, grow up to take care of his parents. A girl, who is often married off at age 13-14, will move to her husband’s family and take care of them. In addition, this is Room to Read’s effort to keep girls out of the sex trade.

Note: There are other NGOs in Laos that build schools, including organizations from the UN, the EU and Japan.

We also learned that Room to Read has a staff in Laos that is passionate about what they do. We left the meeting in the early evening in preparation for a full day of travel by both air and 4-wheel drive as we headed north.

November 28, 2010

Having spent the night in a completely adequate guesthouse in Oudomxay (adequate if you don’t mind sharing the bathroom with lizards and worms, that is), I head out with our Room to Read guide for an authentic Lao breakfast. Sonepraseuth Niradsay, known to us as Tino, attended university in Melbourne and at the age of 25 is Room to Read’s senior associate of communications and documentary. He assures me the noodle soup that we are about to have is quite good. I am on my own for this adventure, leaving Al to have a pancake at the guesthouse since his stomach has not quite recovered from street vendor fare in Vientiane.

Down a dusty side street, the store front is crowded with people at long wooden tables. Women gather around a steaming cauldron; their patrons wait patiently to be served. First each table is given one or two piles of fresh greens -- lettuces and green onions -- followed by rolls of toilet paper (these are what pass for napkins in most eateries in Laos). Then a basket with chopsticks and soup spoons are placed in front of us. Tino takes a spoon and chopsticks and wipes them down with toilet paper, a routine that Al and I adopt for every meal on the rest of our trip. Finally the soup bowls arrive -- steaming broth with bits of beef, a large mound of noodles and a spice ball. Tino explains how I’m supposed to stir it all up, add more spices from the bottles and shakers on the table and pile in as many fresh vegetables as I like. I just stir and taste. Not quite the scrambled egg and toast I’m used to, but it’s okay.

Today is a travel day. It will take us five to six hours (if we’re lucky) on mostly dirt roads to reach Boun Neur, the town nearest the Vangdoy Primary School that Al and I built in 2009 and will visit on Monday. But first, we drop in on Room to Read’s officer for the Girls Education Program (GEP) in Oudomxay. Phatpasa Meksavanh is hosting girls from four schools in a series of weekend classes.

The petite woman has a smile as broad as the sky and a command of English that is quite remarkable. She explains that in all she has 390 students participating in the GEP this year. The ones we get to watch are from grades 5-7, ages 8 to 16.

The GEP scholarship recipients are encouraged to take these special classes held only five weekends a year, from 8 am to 4 pm on Saturday and Sunday. They are taught by Room to Read social mobilizers who also monitor the girls in the program on a weekly basis. The classes are in life skills that can help them get jobs, negotiate pay and feel comfortable around people like us.

For example, one of the classes is crowded with teenagers being taught to say no. Another is teaching girls to laugh freely, audibly, without covering their mouths and pulling back. And a third class has the girls talking about confidence building in small discussion groups.

The classrooms are crowded, the girls’ eyes are bright with the fun they are having. Outside on the school’s open verandah, they have piled identical backpacks, which Room to Read provides. Bicycles are also given to girls who have to travel 2.5 km or more to get to school (and whose families cannot afford one on their on). And for some of the girls, parents have pooled their resources and labor to build dorms on campus because the distance the girls must travel to school is too great to make daily.

Phetpasa Meksavanh, Girls Education Program Officer.

Parents participating in the girls education program watch an emotional film about spousal abuse.

In one of the assertiveness classes, an exceptionally beautiful young girl catches my eye. I remember that one of Somphet’s goals for these classes is to keep girls out of the sex trade, the human trafficking business. For me the subject is now personal. I don’t want to see this child abused.

Across campus in another classroom, parents have gathered to watch a movie about domestic violence. There are perhaps 50 parents in attendance, intently watching a father become abusive after drinking alcohol and a mother beat her child after a stressful day. Some of the parents are openly crying. We are told that the parents will break into small discussion groups after the movie, an effort to create community solidarity and understanding around a difficult topic.

From our quick visit here at the Kor Noy school, we head north into the Phongsaly Province. Six or so hours of bouncing around on dirt roads leaves the kidneys and spine well massaged. As a distraction, I try to concentrate on the passing landscape -- a collection of proud peaks covered with dense jungle, rice paddies glistening in valleys, rivers running peacefully from village to village. While the land is beautiful, the poverty in which its people lives is striking.

November 29, 2010

835 km (16 hr drive) north of Vientiane

Population 317, 101 households

Rice farmers, also grow corn, sugarcane and rubber for export to China

Accessible year-round

Vangdoy Primary School

Grades 1-5 – approximately 18-20 students per grade

Buildings – 2 (1 bamboo hut, 1 new construction)

New building – 3 classrooms, 1 reading room

Teachers – 5, one out on maternity leave

Mr. Kamphan Khod – Vangdoy Primary School Director and 5th grade teacher

Our destination today is Vangdoy, a small village in northern Laos not far from the Chinese border. There are only 101 households scattered around a relatively flat, dusty patch of land along a river. It is on the edge of this village, not far from the river, that we step out of our van and into the welcoming ceremony of students, teachers, village elders and parents at the Vangdoy Primary School.

Children carrying flowers and paper leis form a path up to the schoolyard where everybody else awaits our arrival. With big grins and many kop chais (thank yous) Al and I make our way forward, stopping to collect the proffered flowers and leis. The kids giggle as they struggle to fit their small necklaces over Al’s head.

Introductions complete, the children scatter to their classrooms, and Al and I head for the fifth grade to observe the students. They are reading aloud, one at a time, sharing one book between two students. As each child reads, voices rising up and falling down in the gentle pattern of the Lao language, I take note of the decor. A variety of posters – world flags, a map of Laos, geometric shapes – make colorful splashes along the walls. The shelves at the back of the room carry class projects – woven baskets – and tools for different subjects. The abacus stands out.

Student papers and drawings hang from string that crisscrosses the room. This evidently is Lao tradition. Every classroom we visit, from grades 1 through 5, showcases student work this way.

What we encounter here shapes my thinking about future donations. Vangdoy had an incomplete primary school when the village applied for a new school. What was approved for construction was an incomplete school: 3 classrooms for grades 1-3 plus a reading room. But with the new building, the village attracted more students from neighboring villages, more teachers were assigned to the school, and the place turned into a complete primary with grades 1-5. Problem was, they outgrew the new school by the time the new term started.

So grades 1 and 2 now share a classroom and grade 3 meets in an old bamboo and dirt-floor structure. Clearly the villagers want to fix this by adding two more classrooms. I don’t see the value of ever building something less than a complete primary from now on.

We walk down to observe the first and second graders who are reading aloud from textbooks, nearly one per child. They shyly look at us, big eyes examining these foreign intruders. I can’t help but grin, some of them grin back. A chart next to the door records the children’s ages, weights and heights as of September 2010, the beginning of the school year. Ages for these first and second graders range from 6 to 11, but none seems as old as that. They are all so tiny. I learn as the days go by that I cannot compare these children’s size with what I know of U.S. children. Poverty and diets make for very clear differences.

Moving outside, we visit a teacher’s dorm – a dirt floor and bamboo structure much like the dorm shared by 11 girls at the Kor Noy school we visited yesterday. Not many villagers have anything better; this is the country’s rural standard.

The third grade classroom is about the same (dirt floor, bamboo siding, grass roof). When we step in to observe, they are studying math. One boy is asked to step to the blackboard and multiply 2 times 700, then 4x200. Just for us, the teacher leads the class in a song with clapping. Everybody smiles at each other. As soon as the song is done, the kids and teacher race out into the schoolyard to perform some stretching exercises with the fourth and fifth graders. Tino and I join in.

At 11 am, a gong is run and school is out for lunch. The morning session runs from 8 to 11, afternoon from 1:30 to 3:30. But today is different. The donors are here for lunch and a Basi ceremony.

While lunch is being set up, several villagers take us on a walk down to the river to show us how they generate electricity. A series of drums are set up to rotate with the falling water. The resulting energy is fed into a battery/generator that stores the electricity to be used by the entire village. One of the remarkable things about rural Lao life is that almost everybody has a satellite dish and television.

Back at the schoolyard, the third grade classroom is turned into a banquet room with the desks doubled up and stretched out in a single line. After a number of toasts with the local liquor (lao-lao), we share a meal of sticky rice with hot sauce, grilled chicken and fish. The lack of a common language is a barrier, but Tino is a quick and agile translator, and somehow we manage to share quite a bit of information.

We walk down to observe the first and second graders who are reading aloud from textbooks, nearly one per child. They shyly look at us, big eyes examining these foreign intruders. I can’t help but grin, some of them grin back. A chart next to the door records the children’s ages, weights and heights as of September 2010, the beginning of the school year. Ages for these first and second graders range from 6 to 11, but none seems as old as that. They are all so tiny. I learn as the days go by that I cannot compare these children’s size with what I know of U.S. children. Poverty and diets make for very clear differences.

Moving outside, we visit a teacher’s dorm – a dirt floor and bamboo structure much like the dorm shared by 11 girls at the Kor Noy school we visited yesterday. Not many villagers have anything better; this is the country’s rural standard.

The third grade classroom is about the same (dirt floor, bamboo siding, grass roof). When we step in to observe, they are studying math. One boy is asked to step to the blackboard and multiply 2 times 700, then 4x200. Just for us, the teacher leads the class in a song with clapping. Everybody smiles at each other. As soon as the song is done, the kids and teacher race out into the schoolyard to perform some stretching exercises with the fourth and fifth graders. Tino and I join in.

At 11 am, a gong is run and school is out for lunch. The morning session runs from 8 to 11, afternoon from 1:30 to 3:30. But today is different. The donors are here for lunch and a Basi ceremony.

While lunch is being set up, several villagers take us on a walk down to the river to show us how they generate electricity. A series of drums are set up to rotate with the falling water. The resulting energy is fed into a battery/generator that stores the electricity to be used by the entire village. One of the remarkable things about rural Lao life is that almost everybody has a satellite dish and television.

Back at the schoolyard, the third grade classroom is turned into a banquet room with the desks doubled up and stretched out in a single line. After a number of toasts with the local liquor (lao-lao), we share a meal of sticky rice with hot sauce, grilled chicken and fish. The lack of a common language is a barrier, but Tino is a quick and agile translator, and somehow we manage to share quite a bit of information.

Our Village Tour

Our first Basi Ceremony

Water Driven Electric Generators

Lunch in an old Classroom

The third grade teacher has been teaching for 22 years, but only one year here at Vangdoy. The Ministry of Education rotates teachers from district to district, province to province, giving them annual reviews and new assignments or the same one. She likes the new building and wishes she had one for her students, pointing out how it offers better protection from wind and rain as well as better light – overall a better learning environment than the hut we are eating in.

After lunch we meet with the building committee – six villagers and two teachers, most of whom have children in the primary school. This is the group that is responsible for the ongoing care of the building. To get things started, Al asks why they applied for a school in the first place. The huts that served as school rooms were, they explain, in constant need of repair and had essentially to be rebuilt every year. In addition, when it was too cold or rainy, school had to be cancelled.

By applying for help to the district, they eventually landed at Room to Read. A construction committee, made up of 12 members from every union in the village, was formed to monitor each phase of the process (site clearing, materials purchase, labor etc.). They met every two to three days during construction, which began June 15, 2009, and finished August 20 that year.

On any given day they had 15 to 60 people working at the site. Work began by clearing and flattening the land, which had to be tested by the state to ensure it was clear of unexploded ordinance – a federal requirement for all new construction in Laos. In all, they say they had 800 people from two villages working the site. Something must have gotten lost in translation, so when pushed on that head count, they explain that every time someone showed up to work they were counted as a new person.

Skilled labor was brought in and paid for jointly by Room to Read and the village. To manage the funds, the committee had a system whereby three people had to sign the checks. The most costly items were things that could not be found locally – roofing, cement, steal and brick.

Wanting to maintain the school in good working order, the building committee erected a fence to keep animals out and created a cleaning schedule as well as a plan for annual painting and a security force to keep it safe in summer.

The building is a source of pride for the village, and the school has attracted new students from surrounding villages. Even so, they want more: two more school rooms and running water for the school toilets (the kids currently go down to the river to fill flush buckets at the start of each school day).

After lunch we meet with the building committee – six villagers and two teachers, most of whom have children in the primary school. This is the group that is responsible for the ongoing care of the building. To get things started, Al asks why they applied for a school in the first place. The huts that served as school rooms were, they explain, in constant need of repair and had essentially to be rebuilt every year. In addition, when it was too cold or rainy, school had to be cancelled.

By applying for help to the district, they eventually landed at Room to Read. A construction committee, made up of 12 members from every union in the village, was formed to monitor each phase of the process (site clearing, materials purchase, labor etc.). They met every two to three days during construction, which began June 15, 2009, and finished August 20 that year.

On any given day they had 15 to 60 people working at the site. Work began by clearing and flattening the land, which had to be tested by the state to ensure it was clear of unexploded ordinance – a federal requirement for all new construction in Laos. In all, they say they had 800 people from two villages working the site. Something must have gotten lost in translation, so when pushed on that head count, they explain that every time someone showed up to work they were counted as a new person.

Skilled labor was brought in and paid for jointly by Room to Read and the village. To manage the funds, the committee had a system whereby three people had to sign the checks. The most costly items were things that could not be found locally – roofing, cement, steal and brick.

Wanting to maintain the school in good working order, the building committee erected a fence to keep animals out and created a cleaning schedule as well as a plan for annual painting and a security force to keep it safe in summer.

The building is a source of pride for the village, and the school has attracted new students from surrounding villages. Even so, they want more: two more school rooms and running water for the school toilets (the kids currently go down to the river to fill flush buckets at the start of each school day).

When our interviews are done but before we leave, the building committee, teachers and village elders gather in the library to offer thanks through a Basi ceremony. This is a Lao tradition involving everybody sitting on the floor, prayers by a spiritual leader, toasts of thanksgiving and cotton strings tied to our wrists. After the prayers and toasts, every village participant picks up strings from a low table set with fruit, cookies and candy. They then proceed to tie a piece of string on each of our wrists, wishing us a long and heathy life. According to Tino, we are supposed to leave the strings on for three to seven days. It is a beautiful ceremony, which we enjoy at each school we visit.

November 30, 2010

693 km (14 hour drive) north of Vientiane

Population 534, 78 households

Grow rice and sugarcane

Access difficult in rainy season due to mud slides

Sopkay Complete Primary School

Grades 1-5, approximately 100 students from 7 villages

Buildings – 1 (next to an older secondary school)

Teachers – 5 (one out sick)

Total cost – 282 million kip

Community’s share – 34 million kip

It is a short ride from our hotel in Khoa to Sopkay Village, just 25 minutes down the paved road that also leads to Vietnam. Just like yesterday, children are lined up to greet us with flowers and leis. Because this is the official handover, not just a simple donor visit, the schoolyard is set with banquet tables under two old parachute canopies. Speakers, a microphone and a mixer cut the yard in half, showcasing the new school next to an older secondary school. In front of the school, a large sign welcomes us to the handover ceremony, which Boualikahn begins with a quick welcome speech. Al follows, as do the heads of the seven villages that send their children here. I fear it will be a very long day.

In fact it is, but it’s also one of the best experiences in a foreign land I’ve ever had. The people are so warm and eager to share this special day, to show us everything about the new school and to demonstrate how well the children use it.

After the initial speeches, Al and I move to the grade 5 classroom, where 24 students are studying Lao language. As I’ve seen in U.S. schools showcased on television for good teaching practices, the students are directed to clap when one of them answers a question correctly.

Tino translates the class’s weekly schedule, posted next to the blackboard, into English for me.

On Monday for example they have:

8-8:50 – Demonstration in front of flag

9-9:50 – Lao language

10:10-11 – Lao language

11:10-12 – World Around Us

12-1:30 – Lunch

1:30-2:20 – Traditional crafts

2:30-3:20 – Manners

3:40-4:30 – Activities

Tuesday:

8-8:50 – Physical education

9-9:50 – Math

10:10-11 – Math

11:10-12 – Lao language

12-1:30 – Lunch

1:30-2:20 – Music

2:30-3:20 – Manners

3:40-4:30 – Activities

Interestingly, on Thursday they study English for two hours. The teacher makes one of the boys stand and recite the ABCs for us. With a bit of coaching he nervously makes it through.

One room over, we visit the combined classroom of grades 3 and 4. Grade 3 (ages 8-12) has only 12 students, but grade 4 (ages 9-13) has 20. All the classrooms we visit note attendance on the blackboard, including how many girls versus boys are in the class. All the numbers are pretty close to even.

As in other classrooms, there are colorful posters of world maps, the alphabet, flags of the world, food groups and more. What is unusual and unique to the classrooms of Sopkay are the toothbrushes and toothpaste affixed to the wall next to the door. Every child has his own brush and paste in a pocket. It makes me wonder who has been through the village selling dental hygiene – not that it’s bad, just unusual.

After visiting the second graders (14, ages 17-10), who perform a song and dance for us, Al and I sit down with two girls from the fifth grade: Van, age 11, and Sivon, age 12. When asked which school they like better, the old or the new, Sivon pulls no punches. She preferred the old one because it was “more natural.” Dirt floors and leaky grass roofs are evidently okay with her. When we laugh, she quickly adds that the new one is nonetheless very nice.

The girls are shy and intimidated to be talking with us (no surprise), but we manage to find out that they like Lao and English language classes best, but art class – drawing – is good too. I get Van to draw a tree for me (quite good, really) and to sign and date it.

Van is living with her aunt and uncle in Sopkay so that she can attend school. Her mother lives too far away for her to be able to stay at home during the school year. To help out at home, both girls have chores – cooking rice, feeding the domestic animals (chickens, ducks, pigs) and cleaning the house. But when they are done with homework and chores and they get to play, their favorite pastime is Chinese jump rope.

Construction

Although the library is not open yet, it’s still missing books, this is where we meet with the construction committee, a group of 10 men and three women. This is a lively group, full of back and forth discussion. Thankfully Tino is right there, translating for us.

The Sopkay story is a now familiar one: Unhealthy conditions under the old school and applying to Room to Read. It took five months, 600 workers, 15 to 20 workers on any given day to clear the site of the old school building, transport stone and sand, build the foundation etc. As owners of the land and with the most children in the school, Sopkay provided more labor and funds than the other villages. They used two accountants and required three people to sign checks and supervise the site, finances and materials.

These people feel that they learned a lot and want to share their knowledge with other Room to Read recipients, knowledge about everything from scheduling around the rainy season to clearing the land, managing labor and encouraging local participation.

Their highest costs were for cement, steel and nails. Total cost of construction was 282 million kip, the community’s share was 34 million kip. All this comes from one of the ledgers they have brought to the meeting.

Before we break up, they want to know about Al and I: who we are, what we do, why we are doing this, what schools are like in the U.S. It is a fun exchange, and I am grateful to these people for wanting to know a little bit about us.

Lunch

We take a break from the meetings to have lunch in the Sopkay chief’s home. Men from all the villages pile in. And then there’s me. All the other women are in the next room or serving us. I’m told this is the way things used to be all the time, but no more. It’s just that with all the guests, they revert to form.

We sit on the floor at low tables and enjoy a huge meal of sticky rice, beef, chicken and broth. This is the only meal we have in Laos where desert is served: sticky rice balls cooked in coconut milk then rolled in coconut flakes. Heavenly.

The best part of our lunch break is the walk we take with the chief and several village elders. We stroll down the road and then cross the river on a rickety bamboo bridge to where the village used to be located. Once the government paved the road to Vietnam, households slowly migrated across the river to be closer to commerce. Now all that remains of the site that had been Sopkay for more than 400 years is the temple. They tell us that U.S. bombs destroyed it back in the 1950s, part of the CIA’s secret effort to support France in the Indo-China War. The village was also bombed during the Vietnam War, and a number of unexploded bombs had to be removed before they could rebuild the temple in 1990.

Handover

The official handover ceremony is packed with school children, village members, ministry representatives, Room to Read and us, all gathered under the parachutes at tables covered with colorful sheets sporting Snoopy and China Bear. From the ministry, to the district, to the chiefs, to the principle – each group stands and speaks at a microphone that keeps cutting out and prolonging the speeches. Kaodone, the ministry representative who has traveled with us from Vientiane, says he is happy and proud to be part of this ceremony in such a remote part of Laos. The district speaker says she wants to honor us for helping them and thanks us on behalf of all Laos. Finally, we get to cut the ribbon.

One room over, we visit the combined classroom of grades 3 and 4. Grade 3 (ages 8-12) has only 12 students, but grade 4 (ages 9-13) has 20. All the classrooms we visit note attendance on the blackboard, including how many girls versus boys are in the class. All the numbers are pretty close to even.

As in other classrooms, there are colorful posters of world maps, the alphabet, flags of the world, food groups and more. What is unusual and unique to the classrooms of Sopkay are the toothbrushes and toothpaste affixed to the wall next to the door. Every child has his own brush and paste in a pocket. It makes me wonder who has been through the village selling dental hygiene – not that it’s bad, just unusual.

After visiting the second graders (14, ages 17-10), who perform a song and dance for us, Al and I sit down with two girls from the fifth grade: Van, age 11, and Sivon, age 12. When asked which school they like better, the old or the new, Sivon pulls no punches. She preferred the old one because it was “more natural.” Dirt floors and leaky grass roofs are evidently okay with her. When we laugh, she quickly adds that the new one is nonetheless very nice.

The girls are shy and intimidated to be talking with us (no surprise), but we manage to find out that they like Lao and English language classes best, but art class – drawing – is good too. I get Van to draw a tree for me (quite good, really) and to sign and date it.

Van is living with her aunt and uncle in Sopkay so that she can attend school. Her mother lives too far away for her to be able to stay at home during the school year. To help out at home, both girls have chores – cooking rice, feeding the domestic animals (chickens, ducks, pigs) and cleaning the house. But when they are done with homework and chores and they get to play, their favorite pastime is Chinese jump rope.

Construction

Although the library is not open yet, it’s still missing books, this is where we meet with the construction committee, a group of 10 men and three women. This is a lively group, full of back and forth discussion. Thankfully Tino is right there, translating for us.

The Sopkay story is a now familiar one: Unhealthy conditions under the old school and applying to Room to Read. It took five months, 600 workers, 15 to 20 workers on any given day to clear the site of the old school building, transport stone and sand, build the foundation etc. As owners of the land and with the most children in the school, Sopkay provided more labor and funds than the other villages. They used two accountants and required three people to sign checks and supervise the site, finances and materials.

These people feel that they learned a lot and want to share their knowledge with other Room to Read recipients, knowledge about everything from scheduling around the rainy season to clearing the land, managing labor and encouraging local participation.

Their highest costs were for cement, steel and nails. Total cost of construction was 282 million kip, the community’s share was 34 million kip. All this comes from one of the ledgers they have brought to the meeting.

Before we break up, they want to know about Al and I: who we are, what we do, why we are doing this, what schools are like in the U.S. It is a fun exchange, and I am grateful to these people for wanting to know a little bit about us.

Lunch

We take a break from the meetings to have lunch in the Sopkay chief’s home. Men from all the villages pile in. And then there’s me. All the other women are in the next room or serving us. I’m told this is the way things used to be all the time, but no more. It’s just that with all the guests, they revert to form.

We sit on the floor at low tables and enjoy a huge meal of sticky rice, beef, chicken and broth. This is the only meal we have in Laos where desert is served: sticky rice balls cooked in coconut milk then rolled in coconut flakes. Heavenly.

The best part of our lunch break is the walk we take with the chief and several village elders. We stroll down the road and then cross the river on a rickety bamboo bridge to where the village used to be located. Once the government paved the road to Vietnam, households slowly migrated across the river to be closer to commerce. Now all that remains of the site that had been Sopkay for more than 400 years is the temple. They tell us that U.S. bombs destroyed it back in the 1950s, part of the CIA’s secret effort to support France in the Indo-China War. The village was also bombed during the Vietnam War, and a number of unexploded bombs had to be removed before they could rebuild the temple in 1990.

Handover

The official handover ceremony is packed with school children, village members, ministry representatives, Room to Read and us, all gathered under the parachutes at tables covered with colorful sheets sporting Snoopy and China Bear. From the ministry, to the district, to the chiefs, to the principle – each group stands and speaks at a microphone that keeps cutting out and prolonging the speeches. Kaodone, the ministry representative who has traveled with us from Vientiane, says he is happy and proud to be part of this ceremony in such a remote part of Laos. The district speaker says she wants to honor us for helping them and thanks us on behalf of all Laos. Finally, we get to cut the ribbon.

Cutting the Ribbon

The School handover

Lunch with the chief!

Al speaks, Tino translates.

After the opening ceremony we move back to the library, where we sit on the floor around a low table laden with fruit, cookies, candy, candles and the now familiar white string. A village elder leads the blessings, stumbling over our names, making the entire crowd laugh. With so many people participating, Al and I end up with huge amounts of string on our wrists, but we get into the act too, tying string to villagers’ wrists and wishing them long lives and good health.

From the library floor, we move back outside to begin the feast. With so many tables, so many people, so much food and lao-lao, it is quite the party involving lots of toasts and music and dancing. Al and I are dragged onto the dance floor and taught to do a traditional Lao dance, which amounts to shuffling around in a circle and doing something graceful with our hands. Graceful is not the adjective I would use to describe our moves, but we get out there with big grins and shuffle about anyway.

From time to time, dancing is interrupted by a performance from the school children. The younger performers have to restart several times, but everybody loves their efforts and encourages them with clapping. The older kids look like pros in comparison with their costumes just so and their moves well rehearsed.

By 7 pm, when the chief calls the last dance and we’ve been here for 10 hours, we are well fed and in love with all these people. It was a truly happy day, well spent.

A spectacular feast

Entertainment that started early....

A Young singer

.... and ended late.

Nammatay School set up for a celebration!

Nammatay Village

December 1, 2010

Population 421, 112 households

Grow rice and sugarcane

Access difficult during rainy season due to mudslides

Nammatay Complete Primary School

Grades 1-5, more than 100 students from 7 villages

Building – 1

Teachers – 5 (3 of whom are male)

Total cost – 412 million kip

Community’s share – 53 million kip

Grow rice and sugarcane

Access difficult during rainy season due to mudslides

Nammatay Complete Primary School

Grades 1-5, more than 100 students from 7 villages

Building – 1

Teachers – 5 (3 of whom are male)

Total cost – 412 million kip

Community’s share – 53 million kip

Code of Conduct (posted on school wall)

Obey your teacher

School building is like your second home

Students should love school

Keep bathroom clean at all times

Students should not draw on walls or dirty the floors

Do not destroy school property

Do not touch tables, chairs or books with dirty hands

Do not put feet on walls or tables

No eating or drinking in schoolrooms

Trash should be taken out to bin

Classroom should be cleaned before class starts

It's good for students to grow flowers to decorate the school

Obey your teacher

School building is like your second home

Students should love school

Keep bathroom clean at all times

Students should not draw on walls or dirty the floors

Do not destroy school property

Do not touch tables, chairs or books with dirty hands

Do not put feet on walls or tables

No eating or drinking in schoolrooms

Trash should be taken out to bin

Classroom should be cleaned before class starts

It's good for students to grow flowers to decorate the school

But on this beautiful clear day, the setting is gorgeous: Off the regular road, the northern peaks surround us, a river runs along the valley below, and as we approach Nammatay, a water buffalo ambles through rice paddies glistening in the sun.

With the arrival of the district and ministry representatives, all the same players as yesterday, we are ready to begin another handover ceremony. The people of Nammatay do not disappoint.

Classes

Boualikahn once again opens the ceremony with introductions, Al thanks everyone for the honor of taking part in this special event, and soon we find ourselves observing 22 first graders in the throes of Lao language class. As we move from grade to grade, I’m struck by the fact that there are three male teachers here, one of whom is the chief’s son and is soon to take over as principal of the primary school.

The classrooms are much the same as the other schools: colorful posters of maps, flags, body parts and geometric shapes; strings crisscrossing the rooms showcase the children’s work; special projects in clay (animal figures), bamboo (woven baskets) and wood (pipes) adorn the shelves in back.

I find these children less intimidated by our presence than in the other schools, even with family and friends hanging through the windows to watch our progress. As the second graders struggle with a math problem, I pause and point out an error on one child’s work paper, encouraging him to recalculate until he gets it right.

In the fifth grade the children are set to brainstorm about manners – speaking too loudly, helping elders, brokering a fight between two children. As we watch the kids eagerly debate the topics, Tino points to three small chalk boards leaning against the wall beneath the main board. He translates for us. The first board posts market news, in this case the price of certain goods. The second gives the weather forecast. And the third provides local news, which boldly lists only the Room to Read handover.

Stepping into the library, which still awaits the delivery of books and furniture, we sit down with four students. The three girls (Sivan, On and Ban) are from the third grade. Somlet, from the fifth grade, comes in with his teacher. As the oldest, Somlet is eager to tell us how proud he is of his school, claiming “no other village has a school like this.” They go on to tell us how the old school, made of wood and with a dirt floor, was really cold in winter. We find out later that one teacher is using one of the old classrooms as home, and the village plans to refurbish the other two rooms to be used as teacher dorms as well.

Lao language, math and the World Around Us are favorite subjects with these four, who do not know where the U.S. is and don’t seem concerned that we are from an unknown place. They all have siblings in the school except Somlet. His brother is 14 and no longer going to school. The secondary schools, we learn, are 20 km to the north or 18 km to the south.

As with other children we’ve spoken with, these four help out at home by cooking rice, feeding the chickens and pigs, fetching water and cleaning house. But what do they want to do with all this fine education they’re getting? Ban wants to become a nurse; On and Sivan, teachers; and Somlet, an architect.

Before we leave, they want to know what it is like where we live. We try to satisfy their piqued curiosities by telling them about snow and the mountains, drawing a picture of our differences as well as similarities.

Construction Committee

A very serious group of people from the community sit down with us, the representatives from the ministry and Room to Read to talk about the construction process. So Al starts by asking them to smile or we’ll get nervous. They laugh, and then eagerly get down to telling us their story.

The old school was tiny, overcrowded and inadequate during the area’s more extreme weather. Since they had to pay a lot to keep it in working order every year, they decided it would make sense in the long run to get a new building. Once approved, the villagers elected 16 members to the construction committee. Meeting three to four times a month, they began work on March 15 and finished August 15, employing 600 people, roughly 15 per day.

As with other communities, Nammatay had two accountants and three check signers to keep track of their expenses. The school cost a total of 412 million kip, with 45 million coming from the government, 53 million from the community and the rest from Room to Read.

Using local labor, sand, stone and wood, they purchased the rest of what they needed from Oudomxay and Vientiane, which only proved problematic when heavy rains washed out the roads. But they kept themselves motivated with a spirit of competition, which we find out lives on. They know people in Sopkay, who called and challenged them to put on a better handover party than they had.

With the new school, Nammatay now has five primary school teachers (they only had three before), and two more villages now send their kids here (formerly serving five now seven).

Party Time

Business taken care of we break for our Basi ceremony. Besides the usual fruit, candy, cookies and string, the low ceremonial table also has a pig’s head. Fortunately we weren’t asked to eat any of that, just a banana, before settling into the string routine.

Following the speeches and ribbon cutting, we sit down to dinner – sticky rice, chicken, pork, beef and fish. The music begins and the dancing starts. I swear they are using the same speakers, microphone and mixer that we saw in Sopkay. The chief’s son appoints himself social director, and Al and I don’t get to sit down much.

Before dark, we head into the village with Tino, a couple of village elders and our social director, whose name I finally get: Mr. Xaisamome poses in front of his home with his wife and two children while Al takes his photo. The homes here are quite nice, substantial structures compared with so many other homes we’ve seen. Chickens run squawking across our path, cats and dogs roam freely. We pause to watch two women weaving wall hangings, which they sell to middlemen en route to markets in Oudomxay, Luang Prabang and Vientiane.

The younger villagers have taken over the dance floor while we are gone. Now a few disco tunes are thrown in among the traditional dances. Everybody enjoys the evening – shuffling, jumping, bumping or whatever moves them. One young man introduces himself. He’s a traveling salesman from Vietnam and just happened to be in Nammatay for our celebration. On the dance floor, he grins at me and says in English, “They’re all gettin’ down now.” Getting down, indeed.

Business taken care of we break for our Basi ceremony. Besides the usual fruit, candy, cookies and string, the low ceremonial table also has a pig’s head. Fortunately we weren’t asked to eat any of that, just a banana, before settling into the string routine.

Following the speeches and ribbon cutting, we sit down to dinner – sticky rice, chicken, pork, beef and fish. The music begins and the dancing starts. I swear they are using the same speakers, microphone and mixer that we saw in Sopkay. The chief’s son appoints himself social director, and Al and I don’t get to sit down much.

Before dark, we head into the village with Tino, a couple of village elders and our social director, whose name I finally get: Mr. Xaisamome poses in front of his home with his wife and two children while Al takes his photo. The homes here are quite nice, substantial structures compared with so many other homes we’ve seen. Chickens run squawking across our path, cats and dogs roam freely. We pause to watch two women weaving wall hangings, which they sell to middlemen en route to markets in Oudomxay, Luang Prabang and Vientiane.

The younger villagers have taken over the dance floor while we are gone. Now a few disco tunes are thrown in among the traditional dances. Everybody enjoys the evening – shuffling, jumping, bumping or whatever moves them. One young man introduces himself. He’s a traveling salesman from Vietnam and just happened to be in Nammatay for our celebration. On the dance floor, he grins at me and says in English, “They’re all gettin’ down now.” Getting down, indeed.

Our Interviewees

The village well

I'm glad I wasn't the pig....

Preparing the rice